Phthiraptera

Pronunciation: [PHTHIR-ap-ter-a]

Pronunciation: [PHTHIR-ap-ter-a]

Common Name: Parasitic Lice / Biting Lice / Sucking Lice

Greek Origins of Name: Phthiraptera is derived from the Greek “phthir” meaning lice and “aptera” meaning wingless. The literal translation, wingless lice, is appropriate for all members of the order.

Development: Hemimetabola, i.e. incomplete metamorphosis (egg, nymph, adult)

Taxonomy: Hemipteroid, closely related to Hemiptera and Psocoptera.

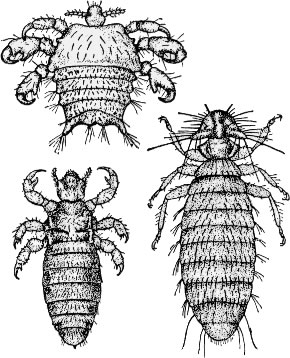

The order is divided into four suborders (Ischnocera, Amblycera, Rhynchophthirina, and Anoplura) distinguishable from one another by the size of the head, the shape of the third antennal segment, and the presence or absence of maxillary palps.

Distribution: Common ectoparasites of birds and mammals.

All Phthiraptera are wingless external parasites of birds and mammals. There is a continuing debate among entomologists regarding the ordinal grouping of these insects. “Splitters” divide them into biting lice (order Mallophaga) and sucking lice (order Anoplura). The distinction is based primarily on the presence or absence of mandibles that are suitable for biting and chewing. “Lumpers” include all parasitic lice in a single order (the Phthiraptera). As justification, they cite numerous similarities in structure and ecology.

The biting lice probably evolved first on birds, feeding on feathers and dead skin cells. But sometime during the Cretaceous period (less than 135 million years ago) biting lice expanded their host range to include certain groups of mammals. A few of these lice (suborder Rhynchophthirina) developed the habit of breaking their host’s skin and feeding on its blood. This lineage presumably gave rise to other sucking lice (suborder Anoplura), all of which are blood-feeding ectoparasites of placental mammals.

Unlike many other ectoparasites, the Phthiraptera cannot survive long if separated from the body of their host. Eggs (called nits) are glued directly to the hair or feathers and nymphs feed on the parental host. Since lice have no wings, dispersal to new host animals is limited to occasions when members of the host species come into direct contact with each other. This close interspecific association means most lice are limited to a very narrow host range — often only a single species.

Appearance of Immatures and Adults:

Sucking lice are responsible for the spread of disease in humans and domestic animals. Pediculosis is an infestation of lice anywhere on the human body. It is usually characterized by skin irritation, allergic reactions, and a general feeling of malaise. In addition, the human body louse is responsible for the spread of relapsing fever (Borellia recurrentis), epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowazeki), and trench fever (Rickettsia quintana). Lice associated with domestic animals have also been implicated in the transmission of disease (e.g., hog lice spread pox virus and cattle lice spread rickettsial anaplasmosis). Biting lice do not usually spread disease pathogens, but heavy infestations in poultry can cause severe skin irritation, weight loss, and reduced egg production.

Philopteridae (Bird Lice) — a large family (500 species) containing several species that are pests of poultry.

Trichodectidae (Mammal Chewing Lice) — ectoparasites of mammals, including pests of domestic cattle and sheep (e.g., Bovicola bovis).

Menoponidae (Poultry Lice) — includes several important pests of poultry (e.g., Menopon gallinae and Menacanthus stramineus).

Haematopinidae (Ungulate Lice) — ectoparasites of cattle, deer, pigs, horses, and zebras (e.g., the hog louse, Haematopinus suis).

Pediculidae (Body Lice) — includes the human body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus) and the human head louse (P. humanus capitis).

Pthiridae (Pubic Lice) — includes Pthirus pubis, the human pubic (or crab) louse.