In some species, each nest contains only a single queen (monogyny) while other species may have several queens living together peacefully in the same nest and sharing in egg production (polygyny). In single-queen colonies, all of the workers are sisters so there is a selective advantage for mutual cooperation. Death of the queen, however, will result in death of the colony because the workers have no way to replace their queen. In multiple-queen colonies, the death of a single queen has less impact. New queens may be adopted or adjacent colonies may join together. Colony survival is maximized at the expense of individual queens who gain no selective advantage if their own daughters are rearing the offspring of another queen.

In some species, each nest contains only a single queen (monogyny) while other species may have several queens living together peacefully in the same nest and sharing in egg production (polygyny). In single-queen colonies, all of the workers are sisters so there is a selective advantage for mutual cooperation. Death of the queen, however, will result in death of the colony because the workers have no way to replace their queen. In multiple-queen colonies, the death of a single queen has less impact. New queens may be adopted or adjacent colonies may join together. Colony survival is maximized at the expense of individual queens who gain no selective advantage if their own daughters are rearing the offspring of another queen.

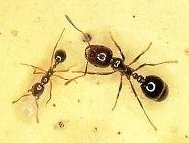

In some ants, all workers are similar in size and appearance. But in other species, workers may vary in size and some individuals may have physical characteristics that make them more suited for some jobs than for others. The smallest individuals, sometimes called minors (or minims), generally work inside the nest caring for the queen or feeding the larvae. Larger individuals may forage for food or enlarge the nest. The largest ants, called majors (or maxims), often have huge mandibles and powerful jaw muscles. They often serve as soldiers, standing guard at the nest entrance, protecting foragers from predation, or defending the colony from raids by other ants.

Pheromones play an important role in the social organization of an ant colony. Alarm, appeasement, social cohesion, recruitment, and trail marking pheromones are among the list of semiochemicals that have been reported in ants. Each colony also has a distinctive taste or odor which members use to identify nestmates and exclude invaders. Regulation of caste is not well-understood. Apparently, all female eggs are identical when laid. Whether they mature into minors, majors, soldiers, or new queens depends on the care and feeding they receive as they grow and mature. To some extent, this may depend on the needs of the colony as manifested through feedback loops involving photoperiod, food supply, temperature, and many other variables.

There are over 8,800 species of ants in the family Formicidae — all of them are eusocial (although some “slavemaking” species no longer have a worker caste). There are more species of ants than all other social insects combined. They are also the most ecologically diverse group in terms of distribution, life history, feeding strategies, and specialized adaptations. As a group, ants consume a wide variety of food, but individual species usually tend to specialize: some are primarily carnivores, some gather seeds and grains, while others concentrate on sweets (nectar and honeydew).

There are over 8,800 species of ants in the family Formicidae — all of them are eusocial (although some “slavemaking” species no longer have a worker caste). There are more species of ants than all other social insects combined. They are also the most ecologically diverse group in terms of distribution, life history, feeding strategies, and specialized adaptations. As a group, ants consume a wide variety of food, but individual species usually tend to specialize: some are primarily carnivores, some gather seeds and grains, while others concentrate on sweets (nectar and honeydew).

In some species, each nest contains only a single queen (monogyny) while other species may have several queens living together peacefully in the same nest and sharing in egg production (polygyny). In single-queen colonies, all of the workers are sisters so there is a selective advantage for mutual cooperation. Death of the queen, however, will result in death of the colony because the workers have no way to replace their queen. In multiple-queen colonies, the death of a single queen has less impact. New queens may be adopted or adjacent colonies may join together. Colony survival is maximized at the expense of individual queens who gain no selective advantage if their own daughters are rearing the offspring of another queen.

In some species, each nest contains only a single queen (monogyny) while other species may have several queens living together peacefully in the same nest and sharing in egg production (polygyny). In single-queen colonies, all of the workers are sisters so there is a selective advantage for mutual cooperation. Death of the queen, however, will result in death of the colony because the workers have no way to replace their queen. In multiple-queen colonies, the death of a single queen has less impact. New queens may be adopted or adjacent colonies may join together. Colony survival is maximized at the expense of individual queens who gain no selective advantage if their own daughters are rearing the offspring of another queen. With more than 8,800 described species, ants are the most ecologically diverse of all social insects. The following list includes some of the more common groups:

With more than 8,800 described species, ants are the most ecologically diverse of all social insects. The following list includes some of the more common groups: