Walking and Running

An exoskeleton can be awkward baggage, bulky and cumbersome for a small animal. To compensate, most insects have three pairs of legs positioned laterally in a wide stance. The body’s center of mass is low and well within the perimeter of support for optimal stability. Each leg serves both as a strut to support the body’s weight and as a lever to facilitate movement.

At very slow walking speeds an insect moves only one leg at a time, keeping the other five in contact with the ground. At intermediate speeds, two legs may be lifted simultaneously, but to maintain balance, at least one leg of each body segment always remains stationary. This results in a wave-like pattern of leg movements known as the metachronal gait. When running, an insect moves three legs simultaneously. This is the tripod gait, so called because the insect always has three legs in contact with the ground: front and hind legs on one side of the body and middle leg on the opposite side. Clearly, it is no coincidence that insects have exactly six legs — the minimum needed for alternating tripods of support.

At very slow walking speeds an insect moves only one leg at a time, keeping the other five in contact with the ground. At intermediate speeds, two legs may be lifted simultaneously, but to maintain balance, at least one leg of each body segment always remains stationary. This results in a wave-like pattern of leg movements known as the metachronal gait. When running, an insect moves three legs simultaneously. This is the tripod gait, so called because the insect always has three legs in contact with the ground: front and hind legs on one side of the body and middle leg on the opposite side. Clearly, it is no coincidence that insects have exactly six legs — the minimum needed for alternating tripods of support.

Coordination of leg movements is regulated by networks of neurons that can produce rhythmic output without needing any external timing signals. Such networks are called central pattern generators (CPGs). There is at least one CPG per leg. Individual networks are linked together via interneurons and output from each CPG is modified as needed by sensory feedback from the legs.

Only animals with a rigid body frame can use the tripod gait for movement. Soft-bodied insects, like caterpillars, have a hydrostatic skeleton. They move with peristaltic contractions of the body, pulling the hind prolegs forward to grab the substrate, and then pushing the front of the body forward segment by segment. This type of movement is exaggerated in larvae of Geometrid moths. While grasping the substrate with their six thoracic legs, they hunch the abdomen up toward the thorax, grasp the substrate with their prolegs, and then extend the anterior end as far as possible. This distinctive pattern of locomotion has earned them nicknames like “inchworms”, “spanworms”, and “measuringworms”.

At very slow walking speeds an insect moves only one leg at a time, keeping the other five in contact with the ground. At intermediate speeds, two legs may be lifted simultaneously, but to maintain balance, at least one leg of each body segment always remains stationary. This results in a wave-like pattern of leg movements known as the metachronal gait. When running, an insect moves three legs simultaneously. This is the tripod gait, so called because the insect always has three legs in contact with the ground: front and hind legs on one side of the body and middle leg on the opposite side. Clearly, it is no coincidence that insects have exactly six legs — the minimum needed for alternating tripods of support.

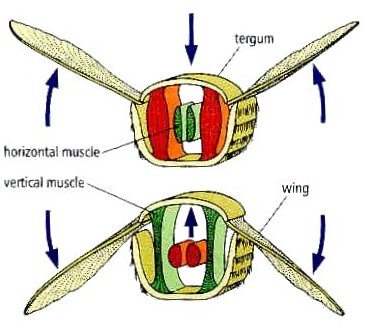

At very slow walking speeds an insect moves only one leg at a time, keeping the other five in contact with the ground. At intermediate speeds, two legs may be lifted simultaneously, but to maintain balance, at least one leg of each body segment always remains stationary. This results in a wave-like pattern of leg movements known as the metachronal gait. When running, an insect moves three legs simultaneously. This is the tripod gait, so called because the insect always has three legs in contact with the ground: front and hind legs on one side of the body and middle leg on the opposite side. Clearly, it is no coincidence that insects have exactly six legs — the minimum needed for alternating tripods of support. Power for the wing’s upstroke is generated by contraction of dorsal-ventral muscles (also called tergosternal muscles). These are called “indirect flight muscles” because they have no direct contact with the wings. They stretch from the notum to the sternum. When they contract, they pull the notum downward relative to the fulcrum point and force the wing tips up. Elasticity of the thoracic sclerites and hinge mechanism allows as much as 85% of the energy involved in the upstroke to be stored as potential energy and released during the downstroke.

Power for the wing’s upstroke is generated by contraction of dorsal-ventral muscles (also called tergosternal muscles). These are called “indirect flight muscles” because they have no direct contact with the wings. They stretch from the notum to the sternum. When they contract, they pull the notum downward relative to the fulcrum point and force the wing tips up. Elasticity of the thoracic sclerites and hinge mechanism allows as much as 85% of the energy involved in the upstroke to be stored as potential energy and released during the downstroke.